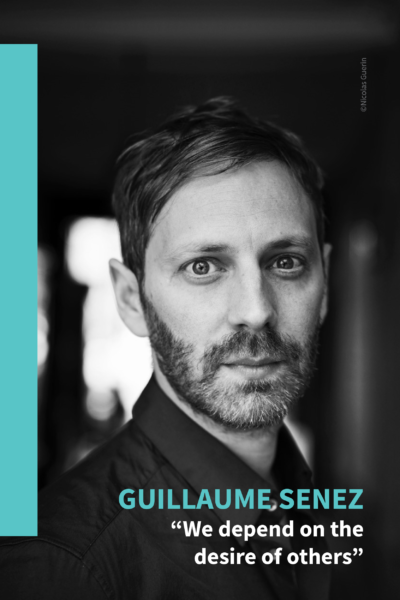

Interview with the Belgian director Guillaume Senez

November 28 2018

Three years after the release of the phenomenal film Keeper, the French-Belgian director Guillaume Senez returns with his new feature film, Our Battles. Although ‘art house cinema’ has its own audience, the director does not hesitate to comment on the lack of funding and a non-existent Belgian star system, which is detrimental for actors and directors.

How do you proceed in writing and choosing your actors?

I do not write for any specific actors; instead it is something I decide once the writing process is completed. I work with two casting directors, one in France and one in Belgium. Even when we receive all available funding means in Belgium, the budget is still not sufficient to be able to comfortably produce a movie and compensate everyone who has participated by legal standards. We are, therefore, obliged to co-produce.

Where did you find funding?

Having the French-Belgian nationality, I logically turned to France for Our Battles. But that is an issue when you want a 100% Belgian cast. For my least feature film, I intended to film everything in the Brussels region. I had about twenty Belgian actors in mind, but due to a lack of (financial) support from that region, we ended up having to film everything in France. Consequently, the Belgian actors dropped out. That is today’s reality. Belgian directors who wish to collaborate with Belgian actors are not always supported by the political authorities. As a director, it then is a logical decision to record a film in a country where we do receive financial support.

That is a pity, because there is plenty of talent in Belgium. I am also working on a short film that will be part of a series of five short films aimed at promoting young, Belgian actors. The directors are already known: Géraldine Doigon, Ann Sirot & Raphaël Balboni, Pablo Munoz Gomez, Laura Petrone & Guillaume Kerbusch, and I.

So, you do not believe in ‘Belgian is the new cool’?

Of course I do believe in that! But it is a reality in the entire world, EXCEPT in Belgium. In fact, there is no ‘star system’ in French-speaking Belgium: a French-speaking Belgian actor must first be knighted in France, so to speak, before he will ever be recognized in Belgium. There exists some kind of Belgian anti-pride, for which we are being praised, but which strongly hinders us on a cultural level in general at the same time, not only on the level of film and cinema. Moreover, this humility greatly reduces our visibility. Many Belgian actors who are known and recognized in the field, are not known with the general public. For that reason, the sector wants to create TV shows, such as La Trêve and Ennemi public, that are supported by our public channels. That is also the reason why we founded the Margritte (film prize). This is clearly some sort of self-recognition which may seem troubling, even though it certainly exists in ALL other countries. The only country in the world in which the media spit on this recognition, is in Belgium. There is very little goodwill coming from our media towards what we are doing.

Was it easier for you to find funding for your projects since the release of Keeper in 2016?

No, not really. Making an art house film stays a challenge and will always remain difficult to finance. For everyone.

In your opinion, are the actors you work with sufficiently aware of their rights?

I think that there are many actors who do not exactly know what neighbouring rights are. Generally, I have the impression that education in Belgian schools is not good enough. Theatre is the focus during the formation of our future actors, but the latter are not sufficiently prepared for audio-visual professions. Together with Catherine Salée, actress and a friend of mine, we often give workshops for students and young professionals who just graduated. This is often an audience that has barely had the opportunity to act in front of a camera. Students have few classes during which they face a camera, and the same goes for dubbing lessons and courses that prepare them for the administrative burden of their future profession. They barely receive any information on what to do when they are unemployed, or about the statute of artists, their neighbouring rights, etc. These young actors often do not know how they come across on the screen, and as a result they are stressed when they stand in front of a camera. In short, young actors are only very little prepared for their profession as actors.

Whom are the workshops that you mentioned aimed at?

These are workshops organized by Brussels Cine Studio, led by Guillaume Kerbusch, and they are mainly intended for young actors, recent graduates, who have not yet created an image of themselves and not know how to perform in front of a camera. We also often see actors who are mainly active in theatre and feel somewhat upset when they are being filmed. The idea here is to “tame” the camera. In the spring of 2019, we will organise a new, innovative workshop with five directors and ten actors. During the previous workshops, Catherine and I realised that there is a great demand from young directors who also want to follow such courses and want to film. We will therefore propose a tripartite approach, in which two actors will work with a director for one day, and the trios will alternate every day. As such, we aim at creating an environment in which actors and directors meet and learn how to work together. In fact, directors frequently do not know how to deal with actors and they are often frightened, and vice versa. Besides experimenting with and in front of the camera, also the way of interacting is extremely important.

In an interview with the newspaper Le Soir you declare that you had to give up your statute as an artist in exchange for an independent statute. Why was that?

A few years ago, the government started a real witch hunt against the unemployed and, consequently, the artist statute. Since 2014, a royal decree regarding the cumulation of copyright and the artist statute is causing us a lot of trouble. Nowadays, many directors are obliged to become independent, as the RVA asks them to pay back their artist’s statute from the point when they receive too many copyrights. There is, however, a huge gap between the copyrights that directors collect, on the one hand, and what he should earn as a self-employed person on an annual basis, on the other. As a self-employed, a certain annual minimum is required in order to keep the head above water, but between this minimum and the limit imposed by the cumulation of rights, there is this no man’s land in which the vast majority of Belgian directors and artists are situated.

At this moment, almost all of us are obliged to become self-employed. And at some point, all these directors will have to make films to avoid bankruptcy, which is completely contrary to the entire essence of being an artist, namely making art because we feel the need and desire to create something. Nevertheless, we find ourselves now in a position that almost forces us to make films for the wrong reasons, that is, to survive. This means that we have to record a new feature film every two or three years. But who will finance these? The Centre du Cinéma of the Wallonia-Brussels Federation already has too many projects going on. Not to mention the danger of films that will increasingly be made according to the consensus and conventions to meet the commercial criteria. That is exactly how creativity and the art house cinema are being killed.

What is it that you do to fight against this?

I am a president of ARRF (Association of French-speaking Directors in Belgium), and one of the things we are working on at present is sensitising the political institutions to initiate changes. Nowadays, being an artist is a daily struggle. So, I fight my war.

What advice would you give the young generation of actors?

Persevere, and that also goes for directors. There are many people out there who want to do it, but only few are the chosen ones. It’s a pity I should say it, but it’s often not talent that counts, but determination. Those who succeed in acquiring fame are those who desire it the most, those who can take the punch and keep going, despite setbacks. We must, therefore, continue to believe in it. It is a profession in which we depend entirely on the desires of others, but actually, we must try and create these desires ourselves. If you are an actor and they do not give you a call, do something YOURSELF: start your own company, set up a spectacle, etc. If you are not the one being chosen for a film, write your own and create your own character. Didn’t you get that role in a theatre play? Make your own theatre piece! I understand that not everybody has the mindset to do this, but it is a recommendation that I would give. Work brings about work, and we must continue to believe, be determined and realise our dreams.